The author, the artist and the Ripper: one woman's mission to find the truth

By Jeremy Laurance

26 October 2002

The most expensive murder investigation ever mounted by a private individual will conclude next week with the publication of a book that claims to identify one of the most notorious killers in history – and is set to scandalise the art establishment.

Patricia Cornwell, the multi-millionaire American author, spent two years and more than £2m on the trail of Jack the Ripper, the Victorian serial killer who terrorised east London by disembowelling five prostitutes between August and November 1888. Cornwell has has crossed the Atlantic half a dozen times, bringing a team of art specialists and forensic science experts to examine letters and artefacts. She claimed on a US television show a year ago that she was "100 per cent sure" that the killer was Walter Sickert, the noted impressionist painter, wit and storyteller.

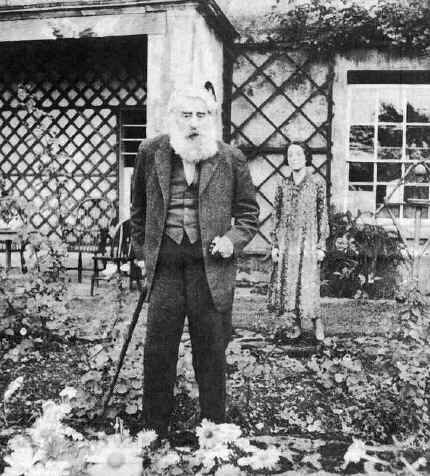

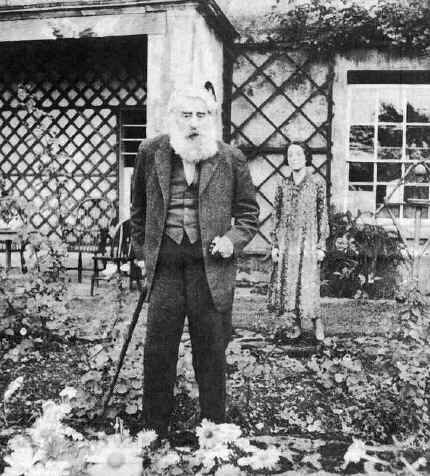

Walter Sickert with his third wife Therese Lessore, St George's Hill House Bathampton 1940

That claim drew a chorus of derision from art critics and commentators who dismissed it as a "crackpot conspiracy theory." Initial efforts by Cornwell's team to confirm the theory by extracting DNA evidence from Sickert's paintings, letters and belongings and comparing them with letters written by the Ripper failed.

But in the last few months, using more sophisticated methods, Cornwell has obtained crucial DNA evidence which she believes clinches the case against Sickert and means his art, examples of which hang in Tate Britain, must be reassessed.

Details of her discovery will be made public for the first time in Britain next week with the release of her book, Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper – case closed, and a BBC Omnibus programme to be broadcast on Wednesday 30th October 2002.

Cornwell's obsession with the Ripper case began when she planned to have her fictional heroine Kay Scarpetta look into the mystery.

She bought 30 of Sickert's paintings and was reported to have torn up at least one in her search for fingerprints or bloodstains, a revelation that appalled the art world. No DNA was found. Sickert's painting table also yielded nothing.

Cornwell fell back on circumstantial evidence. Sickert was known to have a keen interest in the Ripper murders and was first mentioned as a suspect in the 1970s. He produced a series of works known as the Camden Town drawings which showed a clothed man on a bed with a naked prostitute with, in one case, his hands round her neck. He grew up with an abusive father, was a fearful and compulsive child and had a defect of his penis which required surgery and may have left him impotent. He married three times but never had children. Cornwell believes that his sexual dysfunction was a "huge trigger for him".

Physical evidence was essential, however, and the breakthrough came with the examination of a letter purportedly sent by the Ripper to a London newspaper.

The case gripped London in the late 1880s and hundreds of letters were sent to the police allegedly from the Ripper. Most were hoaxes but a few are held at the Public Record Office. Cornwell obtained permission to test these letters for DNA but her scientific team found they had been heat-sealed under plastic, which degrades DNA.

Undeterred, she kept pressing for clues and a former Scotland Yard curator unearthed a missing letter that had never been sent to the archive. Initial tests revealed no DNA but the paper on which it was written carried a distinctive watermark from Perry and Sons, an exclusive stationer of the day. The paper, with its watermark, was the same as that used by Sickert at the time of the killings.

A defence lawyer might have argued that the Ripper letter was not genuine, or that Sickert wrote it as a hoax. But Cornwell was convinced. "The heck with defence attorneys. A jury back then would have said: 'Hang him'," she said.

Her quest for conclusive evidence continued, and after the first tests for DNA failed, she commissioned more sophisticated and more time-consuming tests for mitochondrial DNA. This time the tests yielded a DNA signature on the Ripper letter which matched DNA on the Sickert letters. It was the evidence that Cornwell had been looking for.

The Sickert letters carried a blend of DNA from several different people, reflecting the numbers who had handled them so the match could have been coincidence. But Cornwell, who disclosed the discovery in an interview with ABC News in the US, said she believed it was "a cautious indicator that the Sickert and Ripper mitochondrial DNA ... may have come from the same person".

Cornwell has won the backing of at least one prominent art historian, a Sickert expert, for her theory. If she can persuade a sceptical art establishment, what had been a mystery will transform to a dilemma. For if Walter Sickert was Jack the Ripper how does that change his standing as an artist?

Cornwell is clear: "[Jack the Ripper] doesn't deserve to be mythologised and turned into some hero played by movie stars. And he doesn't deserve to have his art celebrated."

Read Chapter One of Portrait of a Killer

|