|

The Times April 29, 2006 |

|

| Edward Hughes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

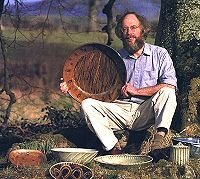

| Studio potter whose work, graced with excellent forms and glazes, was a great commercial success in Japan EDWARD HUGHES was one of Britain’s very finest potters. He has sometimes been called one of studio pottery’s best-kept secrets as, despite the very high quality of his work, he is little known in Britain outside of Cumbria. He did, however, find considerable success in Japan. Thomas Edward Hughes was born in Wallasey in 1953 and grew up in the Merseyside area. He was one of four brothers and it was a very happy childhood. His father, an architect, had hoped that Edward would follow in his footsteps. Hughes’s interest in pottery was inspired by Barry Gregson at Lancaster Grammar School. He later said: “I was blessed to find my vocation when I was 13 or 14.” The school considered that an art career was a waste of time and wouldn’t allow him to take a pottery A level and strongly objected to his plans to apply to art college. His parents, however, were supportive and he managed to take the A level in his own time at the local art school. He then did a foundation year at Cardiff before taking a three-year course at Bath Academy of Art from 1973 to 1976. Hughes’s strong ties with Japan began when he was at Bath. He met his Japanese wife, Shizuko, there — she was studying English literature — and he successfully applied for a two-year scholarship in Kyoto. He spent the first six months learning to speak Japanese and a further 18 months studying pottery at Kyoto City University of Arts. In 1979, at the end of his scholarship, he held his first one-man show. This exhibition was successful enough that Hughes decided to stay in Japan and set up a pottery at Shiga, where he stayed for five years, improving his work all the time. Hughes worked in thrown, functional, reduced stoneware and porcelain — despite the fact that his great love was 17th and 18th-century English slipware and his hero was Michael Cardew. Though he employed some slipware techniques, firing at high temperatures (up to 1,300C) meant that his pots looked much closer to the Mingei style of contemporary studio ceramics fostered by Bernard Leach. Hughes spent a few months in England in 1981 and when he later saw an exhibition in Japan of English slipware he decided to “come back to my roots”. He returned to England in 1984 and set up a pottery the next year on a hillside in Renwick, Cumbria. In 1989 Mary Burkett helped him to establish a pottery in the listed stableblock of Isel Hall, her house near Cockermouth, where he remained. The old tackroom became his workshop and he created a delightful flat on the floor above. Hughes built a downdraught kiln big enough to take about 150 pots, which he usually fired four times a year. By now his pots were some of the best “oriental” work made in Britain. Some potters build their reputation on good forms and others on wonderful glazes. Hughes excelled at both. His shapes — from the smallest saké cup to his huge chargers (thrown from almost 25lb of clay) — had both great solidity and that wonderfully fluid quality that seems to be a hallmark of Japanese training. His glazes were among the most beautiful produced by anybody. Like many potters using reduction firing, he was fascinated by wood-ash glazes. Elm, ash, hawthorn and silver birch would be salvaged from the fires of Cumbrian great houses and his glazes were often named from their origin — “Dalemain”, “Lorton” and “Robin Hood” (the name of his local sawmill). He also worked in tenmoku and produced a spectacular, slightly iridescent, copper-green glaze. Hughes always kept his links with Japan, where he was awarded several major prizes. Every two years he would send up to 500 pots to be exhibited, usually in leading department stores in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto or Kobe. They would all sell — and at much higher prices than could be achieved in England. Most of the pots were bought not by collectors but by people who admired their beauty and intended to use them. He was given an exhibition at the Tomimoto Museum, Nara, in 1999. With such a satisfying market in Japan, Hughes had no great need to sell in England. He was enthusiastic and delightful to be with but felt slightly at a loss as to how to promote his work. This and his higher prices meant that he was rarely exhibited here. His major 1997 exhibition at the Daiwa Anglo-Japanese Foundation in Regent’s Park, London, and another at the Paul Rice Gallery in West London (where the Victoria & Albert Museum acquired a pot) were virtually his only one-man shows outside Cumbria. Edward and Shizuko Hughes were experienced climbers and loved walking in the Cumbrian hills. He died in a climbing accident, after he had gone walking alone and the weather changed abruptly. It is often said that potters rarely reach their peak before the age of 60. As superb as Hughes’s work was, we will, sadly, now never know how great he might have become. He is survived by his wife. Edward Hughes, potter, was born on October 16, 1953. He died on March 31, 2006, aged 52. |

|